E8: Ultracold titanium

Lab rooms: Campbell LL104, Birge B123

Graduate Students: Jackson Schrott, Rowan Duim

Postdocs: Hiro Sawaoka

Undergraduate Students: Kylie Aboukhalil, Clara Castellar

Former Members: Kayleigh Cassella, Andrew Neely, Miguel Aguirre, Diego Pena, Harvey Hu, Lely Tran, Matthew Bilotta, Diego Novoa, Pouya Sadeghpour, Benjamin Capinski, Anke Stöltzel, Scott Eustice

Prospective students: We are always looking for interested students, and hope to recruit a new graduate student in Fall 2026! Check out the information on this page and if you are interested in our work, feel free to contact us at jack.schrott@berkeley.edu or rowan.duim@berkeley.edu!

In recent years, ultracold atoms have become an ideal experimental platform to study novel quantum phases of matter that are governed by quantum mechanics. In our experiment, E8, we are expanding the quantum phases of matter that can be studied by laser cooling and trapping an element with strong anisotropic atom-light interactions: titanium.

Overview: Why titanium?

Elements that have previously been cooled to ultracold temperatures: the simple, spherically symmetric atoms in black, and the complex, magnetic atoms in red. Intermediate atoms (in blue) offer unique properties for quantum simulation.

With any ultracold atomic system, a particular atom's electronic configuration dictates the variety and strength of interactions that can be realized in the system, and thus the phases that can be created. Titanium is unlike all previous laser cooled atoms and its properties will allow us to probe the physics on particles with anisotropic interactions in ways other atoms cannot. These interactions are needed to study novel phenomena such as the fraction quantum Hall effect and topological materials in 2D systems.

To begin it is worth consdiering what can be done with the workhorse atoms of atomic physics, the alkalis and alkali-earth atoms. They all have highly symmetric ground states and consequently a simple spectrum of energy states. Cyclic transitions exist in the ground states of these systems, which makes cooling and trapping them easy. However, the symmetry of the ground state leads to atom-light interactions that are largely independent of both the atomic spin state and the light’s polarization, limiting the strength of anisotropic interactions that can be generated. Creating anisotropic light-atom interactions with these "simple" atoms requires near-resonant light[1], which significantly reduces experiment lifetimes through heating of the atoms.

The other major group of atoms that have been cooled to the ultracold regime are the so-called magnetic atoms: dysprosium (Dy) holmium (Ho), and erbium (Er), which are able to create strong anisotropic interactions with far-off-resonance light [2]. However, the atoms’ large magnetic moments (𝜇gs>𝜇B) creates long-range (dipolar) interactions that, while interesting, severely reduce the length of time that atoms in mixtures of spin states will remain trapped [3]. Without the ability to study spin mixtures, many interesting quantum phases remain unable to be realized using these atoms.

Titanium, and certain other transition metals, present a new atomic system compared to either of the previously studied atoms. A quantum degenerate gas of titanium atomic gas will allow for the realization of anisotropic light-atom interactions with far-off-resonance light in long-lived mixtures of spin states not limited by long-range dipolar interactions. This is possible because titanium’s lowest energy electronic configuration, [Ar]3d 24s2, yields a ground state a3F2 with non-zero orbital angular momentum (L=3), yet a small magnetic moment (𝜇gs=4/3𝜇B). Titanium has many stable isotopes, ensuring the likelihood of finding favorable atom-atom collisions. These properties make titanium an ideal experimental platform for studying many body quantum systems with anisotropic interactions.

How to laser cool titanium

While this ground state is not suitable for laser cooling directly, a metastable state does have a broad, closed transition (λ = 498 nm, 𝛤/2𝜋 = 12.1 MHz) that is ideal for laser-cooling. Using this transition, we laser cool and trap titanium atoms in a magneto-optical trap (MOT), allowing us to reach temperatures of approximately 100 𝜇K.

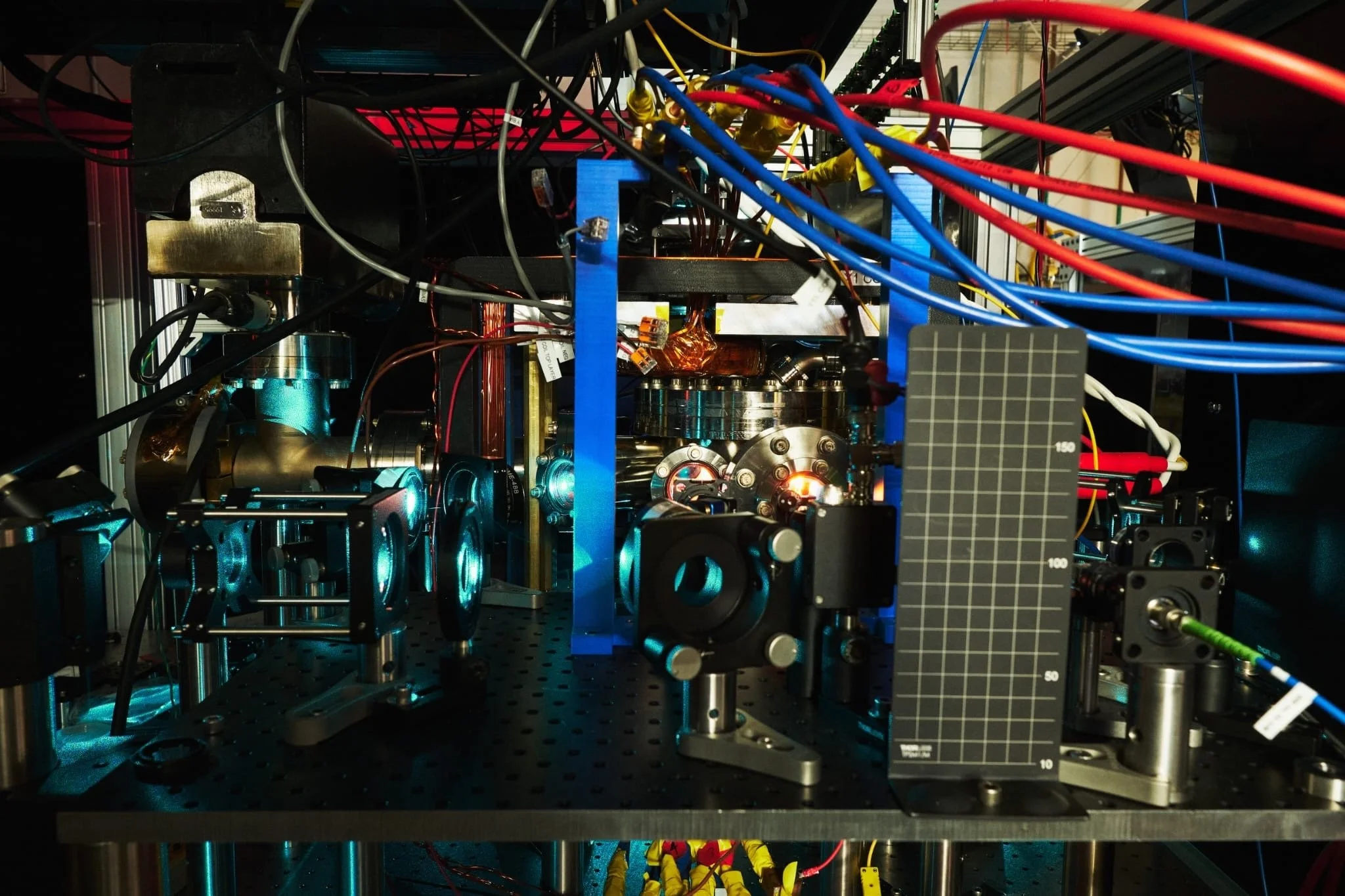

Experimental System

Magneto-optical trap of titanium atoms. The small blue dot in the center of the vacuum chamber is about 800,000 Ti atoms cooled to less than a thousandth of a degree above absolute zero!

Past work in E8 involved developing sources of titanium atoms, which proved to be no trivial task due to the high melting point of Ti! To this end, we developed two sources which generate gas phase titanium: a source based on titanium sublimation getter pumps (TSPs) and a source based on laser ablation of a piece of titanium metal. Currently, we use a TSP as our atom source, but continue to look into alternative beam sources; namely an inductive Ti oven developed at LBNL [4]. Previous work also included a great deal of spectroscopy to identify the atomic transitions that are most of use in cooling and control of titanium. We have implemented standalone lasers that address the transitions of interest, namely several external cavity diode lasers (ECDLs) at wavelengths of 391 nm, 400 nm, 474 nm, and 671 nm. The 391 nm laser optically pumps atoms into the laser coolable metastable state. 400 nm light serves to image atoms in the ground state, while the 474 and 671 nm lasers act in concert to perform efficient optical pumping from the metastable excited state back down to the ground state.

In 2024, we realized the first magneto-optical trap of Ti using a Ti sublimation source [5]! We trap about 800,000 Ti-48 atoms at a temperature of 90 μK. Recently, we have performed spectroscopy on the fermionic isotopes Ti-47 and Ti-49, which possess hyperfine structure, and observed MOTs of these species as well. Current work focuses on developing a second-stage MOT on the narrow (11 kHz) line at 1040 nm. In this narrow-line MOT, we have reached temperatures below 2 μK.

In parallel to ongoing work on the original Ti MOT chamber, we are building a next-generation experiment which will have a Zeeman slower loading atoms into a magneto-optical trap. In this custom chamber with ultrahigh vacuum conditions and Zeeman slowing, we aim to have about 1000 times more atoms! Along with the current efforts on narrow-line cooling and optical trapping, this will allow us to create quantum degenerate gases of Ti.

Jack assembling the next-generation Ti MOT chamber in our new lab space

E8 is an exciting experiment and provides many opportunities for learning everything about building an ultracold atoms experiment! If you are interested in the project, please reach out to rowan.duim@berkeley.edu, hsawaoka@berkeley.edu, or jack.schrott@berkeley.edu!

[1] Y. J. Lin, et. al. Nature, 471:83, 2011.

[2] N. Q. Burdick, et. al. Phy. Rev. X, 6:031022, 2016.

[3] N. Q. Burdick, et. al. Phys. Rev. Lett., 114:023201, 2015.

[4] D. Todd, et. al. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research, Section A, 1072:170183, 2025

[5] S. Eustice, et. al. Phys. Rev. R., 7:023025, 2025